Originally published in the exhibition booklet.

There’s anger in the eyes of the women Amani Haydar paints. There is strength and sadness as well, which by all accounts, is a reflection of her own lived experiences and a theme seen in many of her works; but there’s something different, an immediacy and energy, that’s present in her most recent gallery showing – Painting Flowers at the Peacock Gallery in Auburn.

We have every reason to be angry. The women painted, the two artists responsible for the exhibit, and myself in the audience.

Haydar, a 2018 Archibald finalist and Arab-Australian painter, is known for her work reflecting her advocacy for domestic violence victims. She has spoken publicly and passionately about the 2015 murder of her mother Salwa by her father Haydar in their Bexley home. In recent months, Amani Haydar has opened a broader conversation about the murder of her grandma, her siti, by an Israeli drone.

I’ve felt a connection to Haydar’s work. Her unflinching retelling of her life has always struck me. Her descriptions gave a voice to her mother.

We have a lot in common, more than just our heritage as two Lebanese Australian women.

My grandmother, Mariam Taouk, was murdered almost four years ago by a home invader in her laundry in Jbiel, a coastal suburb of Beirut. She folded my uncle’s pants in her basement washroom and Roy Bou Toubia hit her with a pick axe.

Unlike Amani, there are no colours, beautiful floral prints and embroidery laden canvases when I think about that time.

I have been a passive audience member at previous exhibitions by Haydar, allowing myself to feel the sorrow of lost matriarchs, and now I have been gifted with rage.

Her collaboration with Ms Saffaa, a Saudi Arabian activist and muralist who has confronted issues of Saudi Arabia’s guardianship laws and human rights abuses, offers intensity in a new way that is a mixture of beauty, intricacy and rampant and merciless destruction that we have been forced to endure too many times.

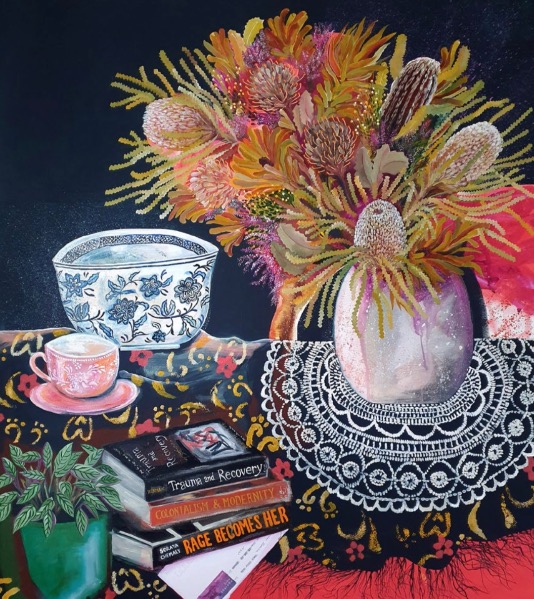

In her portraiture mural, the layered mixed media canvas shows a painting of a simple brown curved vase crammed full of twigs, white open lilies and dotted pink daisies sitting neatly in front of a window framed with an ornately woven white curtain – the kind my siti would have had hanging by her bedroom window, with embroidery twirling over a sheer fabric base. Outside the window is a city of apartment buildings and sky rises destroyed and smoking. There is a fighter jet too – a reflection of the war that saw Amani’s grandmother’s death and her parents’ immigration to Sydney. Beauty coupled with anger. Under the vase sits a rebellious keffiyeh, a symbol of resistance and Palestinian solidarity. Meanwhile Ms Saffaa has become most well- known for her depiction of the shumakh on the head of a woman, emblazoned with #iammyownguardian. Her street art is plastered across Saudi Arabia as a call out for female independence from tyrannical guardianship laws.

In a second piece, a mural of varied faces, the women painted and hanging on the walls have a voice of their own. They glare with burnt charcoal eyes; one is draped in a hijab a sharp purple just like the resilient Lebanese adolya flowers that line the high altitude mountain village paths, sprouting through jagged rock. Another wears a hijab in the reassuring orange of a first responder’s uniform. One has her hair painted pink like bougainvillea, which is a theme in the exhibition; Haydar uses other native Australian flowers to frame the works.

Their rage, shown with thick deliberate lines and wide eyed bold faces are focused, unlike the historic images we have of women and flowers in art; the hidden face or downturned humility of a Degas ballerina, draped in flowers.

“We wanted to create a mural as a tribute to women who have been affected by violence and it was important to me that the figures in the mural represented some of the women who are often underrepresented in conversations about gender-based violence,” Haydar said in an email to me on the eve of the exhibition’s launch.

“Having been myself a victim and a survivor of domestic violence makes this exhibition one that is very close to my heart,” Saffaa also said to me when discussing her collaboration with Haydar.

In Painting Flowers, the two Arab-Australian women, who have had violence and patriarchy impact their lives, are now firmly staring down those responsible. An image I desperately needed to see, to start my own process of healing, moving on from my grief alone.

The exhibition Painting Flowers is as fierce as it is beautiful, shaking off the ideas of women’s passivity in their victimhood. Haydar and Saffaa are telling us that women are not vases watching on as the horrors of the world happen around them – it shows that our anger is justified, and we will be heard.